What, you may be asking, is a Cthulhu, and why is it calling? Well, here’s a picture of Cthulhu, although that hardly does him/it justice. But at least it gives you an idea. The Call of Cthulhu is one of the great stories penned by horror writer H. P. Lovecraft, and is one of many stories he (and others) have written using a cast of horrible, ancient, god-like things that lurk in the dark places of the universe, the mad cultists who serve them, and the desperate people who rise up to battle these blasphemous, abhorrent things. They aren’t horror in the Jason Voorhees style, but

What, you may be asking, is a Cthulhu, and why is it calling? Well, here’s a picture of Cthulhu, although that hardly does him/it justice. But at least it gives you an idea. The Call of Cthulhu is one of the great stories penned by horror writer H. P. Lovecraft, and is one of many stories he (and others) have written using a cast of horrible, ancient, god-like things that lurk in the dark places of the universe, the mad cultists who serve them, and the desperate people who rise up to battle these blasphemous, abhorrent things. They aren’t horror in the Jason Voorhees style, but  more cerebral and disturbing, not gross and bloody.

more cerebral and disturbing, not gross and bloody.

I have been a fan of these stories since the late ’80’s when I first discovered them, and I discovered them through a role-playing game called, appropriately, Call of Cthulhu. And when I refer to a role-playing game, I’m talking the table-top version, with dice and paper and writing implements, not a video game. Lovecraft’s works have yet to be done justice in a video game, but I’ll be there to play it when someone does it right. The closest parallel so far would probably be Silent Hill. It’s close, but not the same, and not part of the same universe.

If you’ve never read any of these stories, I strongly recommend them. And if you don’t trust me, trust Stephen King, H. R. Giger, Brian Lumley, Neil Gaiman, Robert E. Howard, Robert Bloch, Clive Barker, John Carpenter, Guillermo Del Toro and a huge number of Anime and Manga writers. Lovecraft is considered by many to be the most influential writer of all time, beating out Shakespeare and the aforementioned King. And everyone else. If you’ve never heard of him, or never read his works – the works of the most influential writer of all time – you really, really should.

If you’ve never read any of these stories, I strongly recommend them. And if you don’t trust me, trust Stephen King, H. R. Giger, Brian Lumley, Neil Gaiman, Robert E. Howard, Robert Bloch, Clive Barker, John Carpenter, Guillermo Del Toro and a huge number of Anime and Manga writers. Lovecraft is considered by many to be the most influential writer of all time, beating out Shakespeare and the aforementioned King. And everyone else. If you’ve never heard of him, or never read his works – the works of the most influential writer of all time – you really, really should.

My reason for wanting to discuss this topic is two-fold. First, I admire his work, and hope someday to be quoted as saying he was a huge influence on my New York Times bestselling novel-turned blockbuster movie. I want to promote his work, and invite more people to explore a rich and detailed world that looked at horror, fear, and the human condition in a new way.

Second, on Friday, August 23rd 2013 I will be starting up a Call of Cthulhu game with my Friday night gaming group. Similar to Dungeons and Dragons and other similar games, we will sit down and together tell a tale of common people – gangsters and immigrants and scholars and cops – coming face to face with these things, and having to make the choice to lay down their lives – and their very sanity – to stop the evil and save innocent lives. I’ve played this game before, and I’ve even run it before. But I am attempting to tell a very complex story – real-time and with no editing – based only on some notes I have, and my wits.

In role-playing games, someone always has to be the “referee”, “storyteller” or “game-master”. That person is responsible for the majority of the story, and for adjudicating rules and judging the outcomes of actions. It’s never easy, but it can be very fun. Call of Cthulhu, however, is the most difficult game of all to run because it’s 1/3 mystery (with lots of details that must be discovered in musty libraries, and from shady characters in dark alleys), 1/3 exploration (because there’s usually a place where somebody is hiding something, and the heroes have to find it out) and 1/3 action (as the heroes break into buildings, fight cultists and attempt to stop evil high priests). This is a fine balancing act, and at all times every decision has to be made with the goal of creeping out the players.

And let me tell you how hard it is to creep out real people in the room with you. There are jokes, crinkling snack bags, side conversations, and comments putting your story into a usually silly context when compared to the modern-day. In other words, it’s hard for people to take horror seriously when they’re all sitting in a room – safe and sound – together. There are many ways to try and combat this.

I use music as much as I can. Most of the Cthulhu stories are set in the Roaring ’20’s or Depression-era 1930’s, so music can transport people into the story quite effectively, even if only for a little while. I also use props when I can. Nothing drives a player’s imagination quite like when they get to hold a musty old book in their hands and they know it represents a book full of dark knowledge that might drive them mad, but may also help them stop the things.

story quite effectively, even if only for a little while. I also use props when I can. Nothing drives a player’s imagination quite like when they get to hold a musty old book in their hands and they know it represents a book full of dark knowledge that might drive them mad, but may also help them stop the things.

Costumes are part of some of these games, and I’m encouraging their use here. When I run a game that’s in a fantasy setting, it’s more vague in detail, less specific in style and form, so the use of costumes is less effective. But the 1920’s have a unique feel to them – a “flavor” unlike any other time period – a feel that is important to replicate, and so I’ll encourage costumes.

I also use accents and voices. Being a trained actor allows me flexibility that some storytellers don’t have. My friend Andrew used to run a killer game back when he played, but voices weren’t his thing. We all play to our strengths, and having Vinnie “Weasel” Scalatti talking in a certain voice will bring him to life. Knowing that Professor Armitage at the Miskatonic University library often scratches his beard and pulls on his earlobe is worth its weight in gold as far as pulling people into the story.

I also use accents and voices. Being a trained actor allows me flexibility that some storytellers don’t have. My friend Andrew used to run a killer game back when he played, but voices weren’t his thing. We all play to our strengths, and having Vinnie “Weasel” Scalatti talking in a certain voice will bring him to life. Knowing that Professor Armitage at the Miskatonic University library often scratches his beard and pulls on his earlobe is worth its weight in gold as far as pulling people into the story.

When it comes right down to it, however, the best tool I have, the most effective trick I can pull, is to remember what I’ve learned over the years from everyone who gamed with me. I’ll be channeling the spirits of all those who have come before me and been my guide. I might be a good game master, but I got that way because of watching others, and by failing in front of others who allowed me to fail, then helped me up. Most of them would never see this blog post. Some of them are gone now, off to that eternal gaming table in the sky. It doesn’t matter. They’ll be there with me, encouraging me, suggesting details. They’re always there when I run a game, and some day, I hope I stand behind others as they tell their own tales and run their own games.

This is the way it is. I go to run a horror game to thrill and frighten my friends, but I do so as part of all of mankind. Just like the heroes in Lovecraft’s stories sometimes seem alone, but are really soldiers fighting the things together, so it is in our lives in general. Those who have gone before me in this world – and sometimes beside me – are now gone on to live a different life, or an eternal rest. But we are all of us threads in the tapestry of humanity, and none of us – no matter how wise, to paraphrase Gandalf the Grey, can see all outcomes. None of us can see all the tapestry.

I call my teachers and mentors out here, friends, as you must call out those who have guided and sheltered you. Ken, Chris, Dave, Rich, Sherry, Ice cream, Eric J., Hans, Art, Greg, Missy, Tracey, Andrew. There are more, but the ceaseless winds of time have ripped them away from me. They are with me still: They always will be.

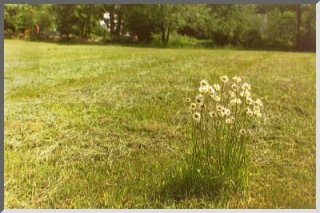

I leave you with a poem, written far better than I ever could. This poem, by Robert Frost, has carried me through some difficult days and nights. I will let it speak for itself.

I leave you with a poem, written far better than I ever could. This poem, by Robert Frost, has carried me through some difficult days and nights. I will let it speak for itself.

The Tuft of Flowers by Robert Frost

I went to turn the grass once after one

Who mowed it in the dew before the sun.

The dew was gone that made his blade so keen

Before I came to view the levelled scene.

I looked for him behind an isle of trees;

I listened for his whetstone on the breeze.

But he had gone his way, the grass all mown,

And I must be, as he had been,–alone,

`As all must be,’ I said within my heart,

`Whether they work together or apart.’

But as I said it, swift there passed me by

On noiseless wing a ‘wildered butterfly,

Seeking with memories grown dim o’er night

Some resting flower of yesterday’s delight.

And once I marked his flight go round and round,

As where some flower lay withering on the ground.

And then he flew as far as eye could see,

And then on tremulous wing came back to me.

I thought of questions that have no reply,

And would have turned to toss the grass to dry;

But he turned first, and led my eye to look

At a tall tuft of flowers beside a brook,

A leaping tongue of bloom the scythe had spared

Beside a reedy brook the scythe had bared.

I left my place to know them by their name,

Finding them butterfly weed when I came.

The mower in the dew had loved them thus,

By leaving them to flourish, not for us,

Nor yet to draw one thought of ours to him.

But from sheer morning gladness at the brim.

The butterfly and I had lit upon,

Nevertheless, a message from the dawn,

That made me hear the wakening birds around,

And hear his long scythe whispering to the ground,

And feel a spirit kindred to my own;

So that henceforth I worked no more alone;

But glad with him, I worked as with his aid,

And weary, sought at noon with him the shade;

And dreaming, as it were, held brotherly speech

With one whose thought I had not hoped to reach.

`Men work together,’ I told him from the heart,

`Whether they work together or apart.’